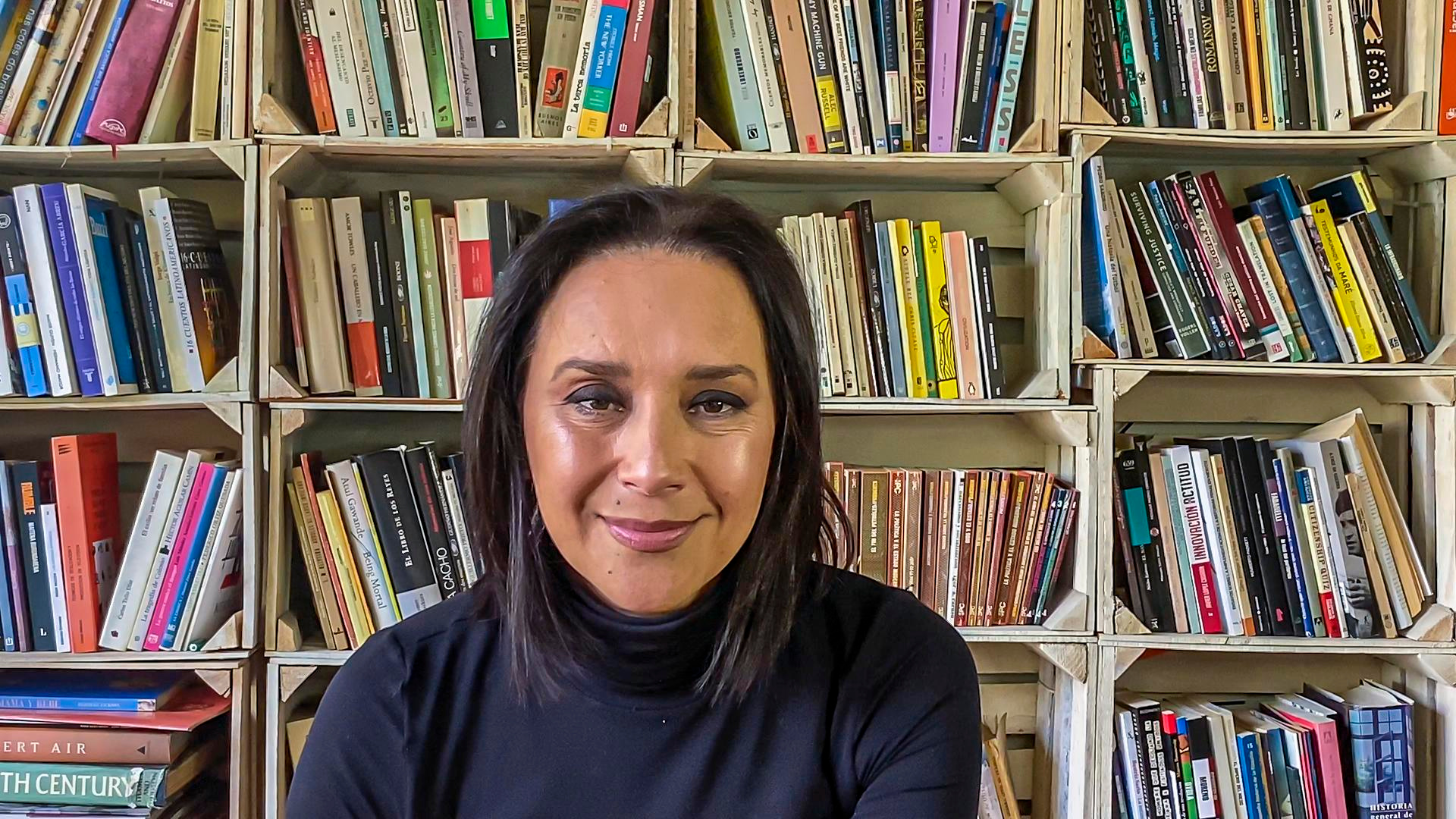

Investigative reporters can trigger social change by showing us how our societies work, and by discovering and pointing out what doesn’t work. Courageous women in this role have ranged from the pioneering female journalists in the U.S. over a hundred years ago, such as Ida B. Wells, Nellie Bly, and Ida Tarbell, to growing numbers of women in many countries today. Karla Iberia Sanchez is one of the most notable. World Woman Hour in collaboration with Organon honors her as a global leader of change — especially for her reporting on women’s health issues and inequality.

In Mexico, Karla’s home country, she is well known to millions who follow TV news on the Televisa networks. Her reports also reach viewers in other nations with Spanish-language news outlets. She has traveled broadly, covering subjects from natural disaster response to the Syrian refugee crisis. She has received international awards and honors. Her award-winning work includes stories on maternal mortality in Latin America, in which she revealed situations where low-income women die when they can’t get proper care during pregnancy or childbirth.

Karla is a strong advocate of in-depth journalism, as well as in-depth thinking and committed action by all of us. Interviewed for World Woman Hour, she argued passionately that complex issues can’t be reduced to “material for getting ‘likes’” in online media, and that stories about human tragedy can’t be reported merely for shock effect: “If you want to change society you have to get to the deepest levels of things. You have to look at how public institutions and others are doing or not doing their jobs.” She also shared some radical (and perhaps surprising) personal views on topics such as leadership for women. Here are the edited highlights.

Q: What led you to your profession?

Karla Iberia Sanchez: When I was a child, I was very curious. My parents told me that at the dinner table, I was always opening the newspaper, even though I didn’t know how to read it yet. Then when I was eight or nine years old, I asked my father to buy me a magnifying glass. I just liked to investigate.

No one in my family was a journalist; I didn’t even know there was a profession called investigative reporter. But then I learned at the National Autonomous University of Mexico, and that is what I became. It’s a passion for finding out what’s really happening. It’s a passion for asking the questions that will show that.

Q: And what stirred you to do the particular kind of investigating that relates to women and health?

Karla: When I’m passionate about public health issues, it’s because I think these issues are a mirror of inequalities in society. The big difference between being an opinion reporter or a talking head and a health reporter out in the streets is that many times, you don’t choose who you will be speaking with. You don’t choose just to talk with a famous politician of the moment or someone who survived a horrendous accident. You go out to find stories of unrecognized pain, of people who are living every day in pain while they are looking for a future.

Many women in marginalized situations are not much older than children, but they are already working for the economic sustenance of the family and they are also the caregivers for the older ones. Even in the middle of a hurricane, they will take public transportation every day to begin work at 7 a.m. and then come back in the night to take care of the family. And then, to see a woman like this at one of the most vulnerable times of her life, in pregnancy and childbirth, being mistreated by public officials—to see her crying outside the doors of a public hospital because she’s in pain, she feels something is not right, and she can’t get in—this is a sign of inequality, and this is a sign of violence against women.

Maybe some editors of the biggest news outlets won’t think that story is important. But I think that story is important. I think it’s important to talk about these 14-year-olds who have preeclampsia because they are not prepared to have a child at that age, for example. Or women who died in El Salvador, because they tried to interrupt their pregnancy with a knife or a coat hanger.

Q: It does seem that we often don’t pay enough attention to the underlying issues in our societies. Could you say some more about that?

Karla: Many times, when reporters are covering violence or forensics, people want to know about the incidents that are the most violent. But violence is not just the 72 migrants killed and buried in a mass grave. [Such mass murders have occurred in Mexico’s drug wars.] Violence is also to know social pain, and to experience the indignities that take away your humanity. Sometimes a reporter can find this coming through in many small details. I remember one day when I was covering a story in a very poor part of Mexico, and I saw a child with a big bandage on her ear. I asked “What happened to you?” and she said, “My grandmother cut my ear with scissors because I was making so much noise.”

This is the violence that kids are facing in the world. And then imagine the horrendous life of that grandmother, that would lead her to do that. So maybe violence is not just the 72 murders. Maybe it’s a child who has a bandage on her ear. Maybe it’s that we have a society where we are so stressed that we can’t even let a kid make noise.

Q: What can the rest of us do to help with issues like poverty, inequality, and systemic violence?

Karla: I think we have to be critical citizens. We have to go out and know what’s going on in the streets. If you are a social scientist or a politician, if you are a postgraduate professional, then you have the tools. You have the tools to transform society, and you have to be out in the streets and really try to understand what is happening.

I think a critical society requires many kinds of observation and social analysis. If you really want to change things you have to be aware of what’s happening with national budgets and legislators. Know your local authorities, know your local leaders and listen to them. To put it in terms of taking positive steps, I would say that what could help to solve these problems is to dedicate more of our time and talents to knowing how society works—and not just criticizing. It’s also finding how to put your own talents and passions to work in the service of others. Not for public exposure, not for posting on Instagram, but for fulfilling the mission of helping others.

Q: If you were to give advice to young women today, who are searching for the best way to have their lives make a difference, what would you tell them?

Karla: I would advise them to follow the fire they feel inside. If you are looking for something that will make society stronger, or make you better, don’t put a cover on your own fire. Don’t smother it just to be comfortable, just to watch another series on Netflix or to spend half an hour more on Instagram. There are moments in life when you feel a burning inside you to do something to make a change. You have to do it, even if you experience enormous difficulties. Sometimes discomfort or even extreme fatigue is not bad. It’s a sign of moving forward.

Q: Finally, we’d like to see more women in leadership positions, whether it’s in journalism or any other field. In your judgment, what does leadership consist of? And how can women prepare to lead?

Karla: There’s no school for leadership. There are schools of management, but leadership is a kind of a transit of yourself. This is the process I have seen in women that I admire. It’s like being in an escalator of yourself. Not an escalator of power, but an escalator of transit to being someone who can have influence in society—and not like an “influencer,” not for being popular. Real leadership is what I see in women who have been swimming into themselves, who have passed through borders into themselves.

It’s not an intention or a project of life to be a leader. Maybe sometimes that works, but leaders to me are people who gain the respect of their colleagues and the respect of society. They are people who look for excellence. Instead of comforting themselves with their egos, they always ask: “What more can I be doing?” This means that leaders also must have a high sense of self-criticism. They have to be good learners. And then they can give advice [that others will listen to]. They are the people who can say, “Let’s stop doing that. Let’s move to a better way of doing things.”